We Believe Philanthropy is Changing

The points of entry have grown more diverse, the attitudes more humble and inclusive, the tactics more sophisticated.

This belief came from our own experience, based on what we were seeing in the field. But were others experiencing the same thing? What did they see happening? Were there opportunities emerging for a new wave of philanthropists?

The more we asked questions like these, the more we felt it was time to document the trajectory of social impact work — to get specific about the attitudes, strategies and sentiments that are shaping its future. On the one hand, we wanted to broaden our perspective and get better at our own work. But we also wanted to provide some context, some common footing, for anyone who wants to make an impact but feels stuck, stymied, or confused about where to start, or is simply curious about what it means to achieve social change.

To get a full lay of the land, we surveyed 692 social impact professionals about why they work, how they work, and what they think will enhance their work. For deeper insights into their mindsets and experiences, we interviewed 15 of our survey respondents, including social entrepreneurs, experts from NGOs, government officials, nonprofit leadership, and people who’ve lived in the face of urban poverty and have found a way out.

We learned that philanthropy is indeed changing. And it’s changing in five distinct ways:

- The role of philanthropy is shifting, from one that focuses on capital to one that focuses on competence.

- The motivation to work in philanthropy is shifting, from passion alone to a mixture of passion and pragmatism.

- The approach to problem-solving is shifting, from staging interventions to pursuing innovations.

- The relationships between social impact leaders are shifting, from coordination among peers to full-on collaboration.

- The scope of work within organizations is shifting, from quick fixes to long-term involvement.

Some of these we’ve sensed and experienced ourselves — the importance of signing up for the long haul, for example.

Most of all, though, we learned that people long for a deeper conversation. They want to know what their peers think and experience. They sometimes feel cut off from each other’s work and worlds, even though there’s a lot of natural overlap. And they’re eager to learn from each other.

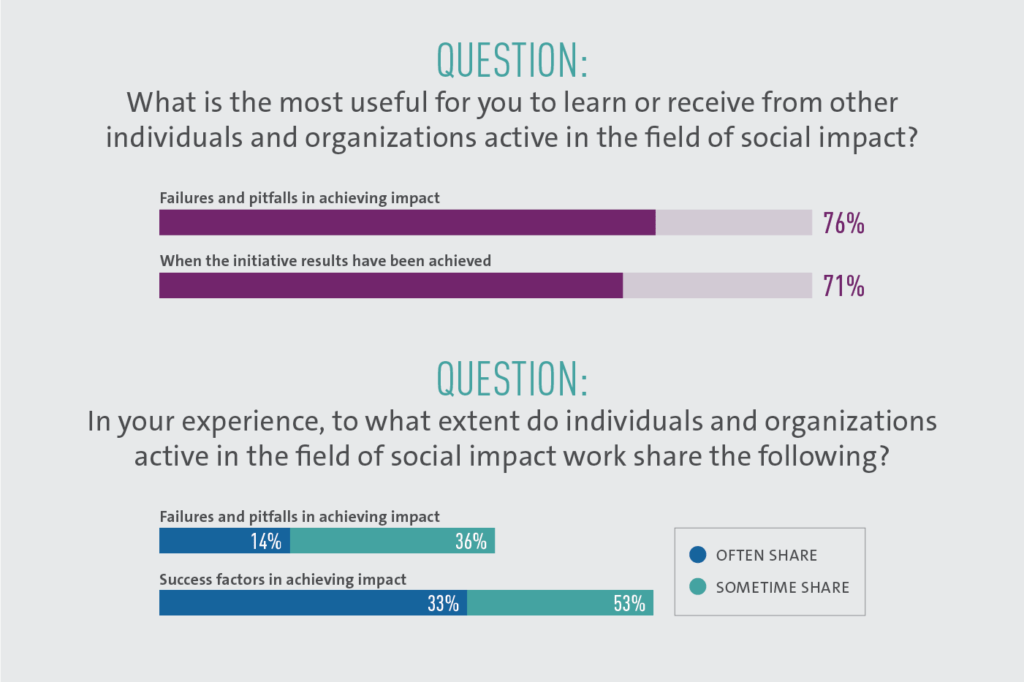

Here’s an interesting insight: In our survey, 71 percent of respondents said it’s useful to learn what makes each other successful in achieving impact. That’s a number we expected and understand. But 76 percent said it’s useful to learn about each other’s failures and pitfalls. And that should catch our attention.

Why are people more interested to hear what’s not working? We want that information because it’s immensely instructive. We all want to know which pitfalls we can avoid in our own work. Most of the time, though, each of us has to find out for ourselves: Only 14 percent of respondents feel that their peers often share their failures. We’re running in parallel, but not in sync.

We hope this report can start to change that. There’s a new calculus for identifying problems and mobilizing solutions. And a stronger consensus than you might assume. Adapting to these shifts, and embracing each other’s lessons learned, will make everyone — us included — more effective.

From Capital to Competence

Once considered the exclusive province of the wealthy, philanthropy now invites — and even demands — a mix of money, time, and talent.

Historically, philanthropy was rooted in “noblesse oblige” — the idea that the wealthy are obligated to put their wealth to good social use. That idea still has merit, but it doesn’t tell the whole story.

Many years on the job have taught us that philanthropy is as much about tapping brains and networks as it is about tapping wallets. Our research confirms this.

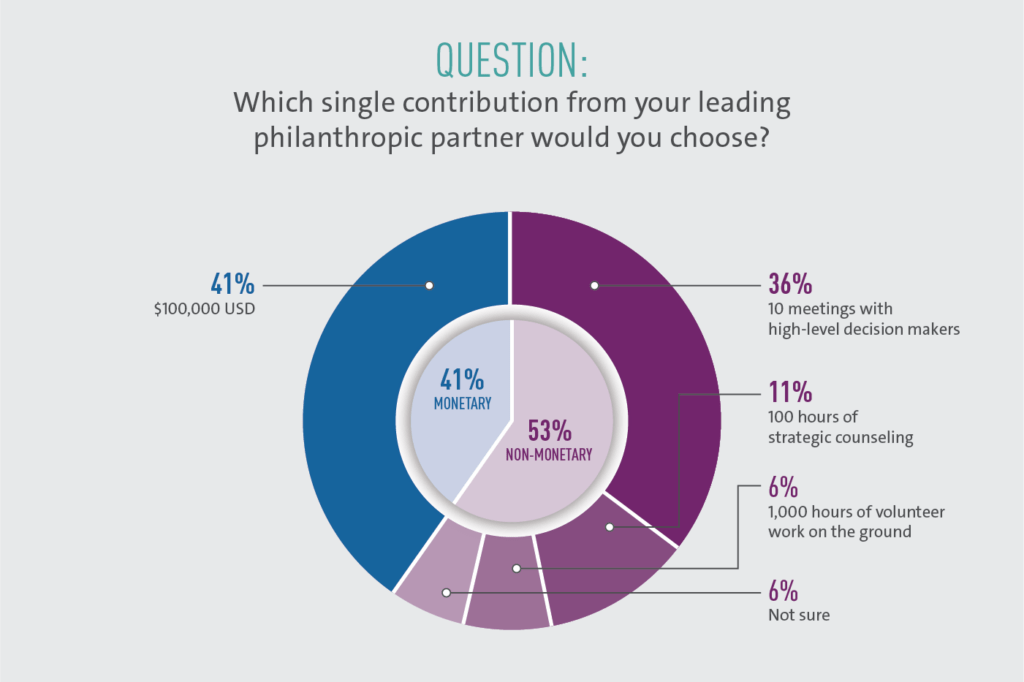

When recipient organizations in our survey were given the hypothetical choice between a $100,000 donation and non-monetary support like strategic counseling, volunteer hours, or introductions to high-level decision makers, only 41 percent of them opted for the money. The majority would rather benefit from collaborative action and advice.

The Rise of the Active Donor

It’s not as though funding isn’t important anymore. When asked about the role of philanthropists, 76 percent of respondents pointed to their ability to contribute funds directly to a cause, and 57 percent noted their value in helping to secure funding from others.

Yet the majority of our survey respondents felt donors should contribute in other ways as well, whether that is by providing access to their networks (56 percent), sharing strategic direction and support (51 percent), or assisting with enhancing visibility and advocacy (50 percent). Increasingly, it seems, there is a desire — an expectation, even— for major donors to do more than just cut a check.

“It’s not just about looking for the capital, but also looking for people to have on a board of directors or get involved with how strategy is shaped,” noted Vikram Gandhi, founder of Delhi-based Asha Impact,

which helps business leaders better leverage their own expertise, capital and networks to collaboratively address critical development challenges.

Time and time again, our interview subjects told us that in the best partnerships, donors participate as thought leaders, problem solvers, and listeners.

Finding New Applications for Old Skills

A new demand for investment via money, talent, and time in social impact work implies that there is no monetary prerequisite or price of entry for contributing to the landscape. Many of the sector professionals we interviewed stressed the need to challenge people’s assumptions about how they can contribute to a cause.

“We all have the ability to contribute to society, whether it’s volunteering in church or doing something through your marketing job at some company,” noted Erin Mote, co-founder of Brooklyn LAB and executive director of InnovateEDU, a New York City-based nonprofit focused on closing the achievement gap in K-12 education. “You don’t have to have a million dollars to make an impact.”

If you have a job where you’ve worked for 10-15 years, you probably have a lot to contribute. A lot of young organizations can really use that wisdom.

Ruchit Nagar, Co-founder and CEO, Khushi Baby

Among those we interviewed, a common piece of advice for today’s would-be philanthropists was to think more creatively about how old skills could be applied in new settings. Indeed, in our own work at the foundation, we have encountered countless organizations of all sizes eager for both strategic and executional support, in everything from operations management to product development, communications and advocacy. It is a rare organization in today’s landscape that will turn away an offer for extra brains or hands.

Ruchit Nagar, co-founder and CEO of Khushi Baby, a technology nonprofit focused on maternal and child health in India, put it this way: “If you have a job where you’ve worked for 10-15 years, you probably have a lot to contribute. A lot of young organizations can really use that wisdom. And if your expertise isn’t relevant, maybe you have some great idea or the capacity to execute.”

From Passion to Pragmatism

Philanthropists increasingly realize the imperative of getting to the core of an issue before jumping to solutions.

People aiming to solve society’s big challenges start their work with good intentions. But in today’s social impact landscape, there is an increasing recognition that good intentions alone aren’t enough. According to our research, in choosing how to make an impact, people must consider not just what they want to do, but what the situation calls for them to do.

Matching Passion, Talent, and Cause

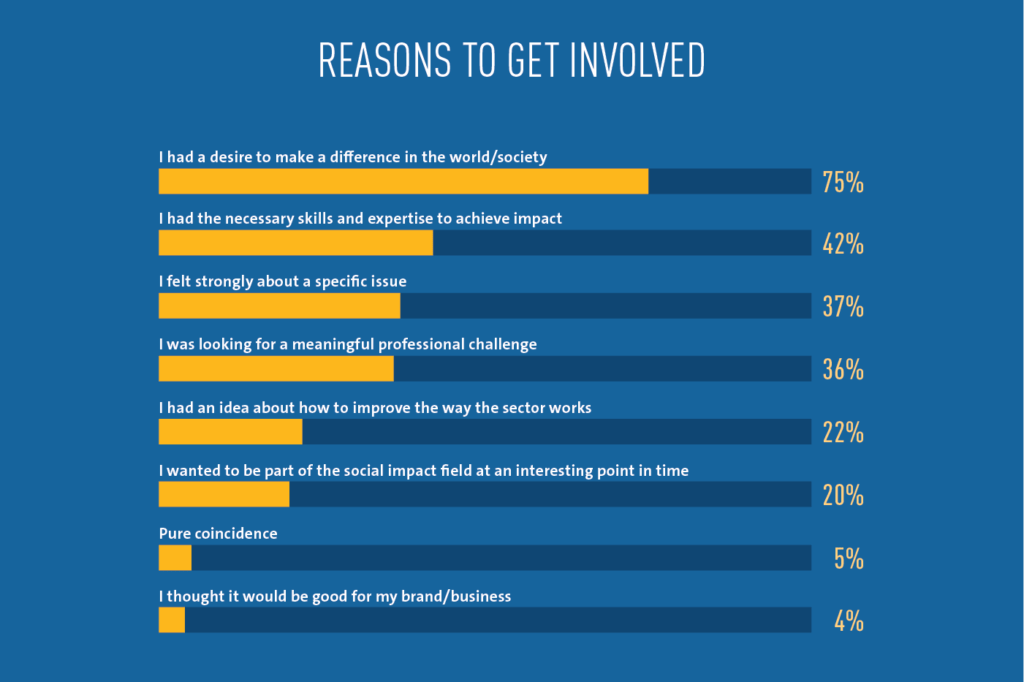

Perhaps not surprisingly, 75 percent of our survey respondents said they initially jumped into impact work because they wanted to change the world. However, many were light on the details of how to do so. In fact, only 42 percent noted their specific skills or expertise as their primary motivation.

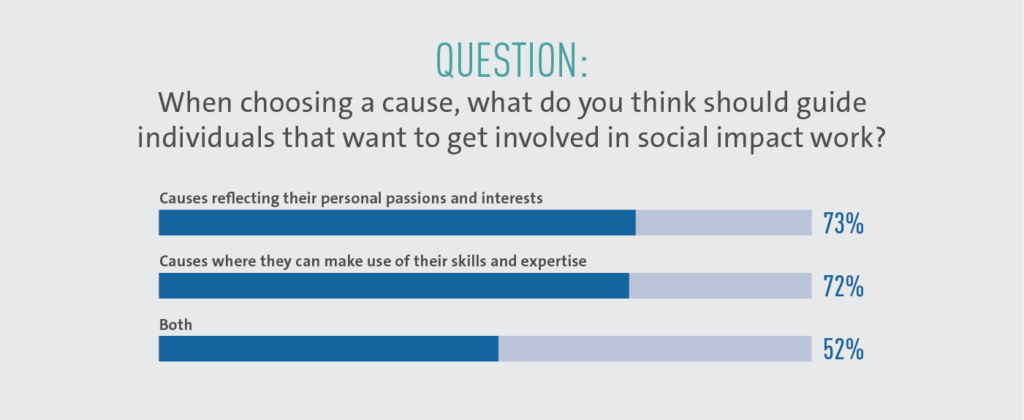

Today, however, that naiveté is being replaced by a much more pragmatic mindset. When asked what should guide future philanthropists in choosing a cause, survey respondents cited passion and expertise in almost equal proportions (73 and 72 percent, respectively). More than half (52 percent) of our respondents selected both options, suggesting a sweet spot at the intersection of desire and know-how.

Stephen Mahony, founder of The JumpStart Foundation, which provides language, literacy and social-emotional programs for disadvantaged school children in South Africa, advised future philanthropists to find ways to apply their skills practically: “Only following one’s passions may not necessarily address what most needs doing in the long term.”

Getting to the Root of the Problem

Of course, finding that intersection of passion, skill, and need requires impact practitioners to dig deep into the issues they want to address. Those we interviewed emphasized the need to start projects with a robust course of discovery and to keep a close ear to the ground over time.

Some philanthropists don’t fully grasp or have an understanding of the actual problem — and it could result in them causing more harm than good.

Thashlin Govender, Program Director, Dell Young Leaders

“Some philanthropists don’t fully grasp or have an understanding of the actual problem — and it could result in them causing more harm than good,” notes Dr. Thashlin Govender, program director of Dell Young Leaders, a university success program in South Africa. “It’s very important to understand the problem.”

Jennifer Carolan agrees. The co-founder and general partner at Reach Capital, a venture fund focused on early-stage high-impact education technology startups, noted that one of the most critical values guiding her organization’s investments is humility. “We don’t operate with the idea that we have the answers,” she noted. “We don’t have all the answers to these challenges that people have worked with for decades, and we don’t have the hubris to think we can solve these challenges just like that.”

Other respondents emphasized that the process of fully understanding societal challenges includes seeking perspectives from diverse sources. When asked where the best ideas for social change will come from in the next decade, 62 percent said they will look to social entrepreneurs, 40 percent to those people living with and facing these challenges, and 32 percent to local NGOs. More “traditional” entities like governments, academic institutions, and international NGOs fell at the bottom of the list.

From Interventions to Innovations

As the social impact sector’s appetite for risk grows, creative new ways of approaching problems are replacing old-school, prescriptive efforts.

Sometimes progress comes slow and steady. Other times it takes a big leap forward. While there is no easy formula for predicting or producing breakthroughs, today’s impact landscape is more focused than ever on accelerating the pace of innovation for the greater good.

Partners in Risk

No organization has a monopoly on risk or innovation. But when it comes to the leeway to invest in risk, philanthropic foundations may have an upper hand. In our survey, 53 percent of respondents noted that such organizations are better equipped than others to provide seed funding for innovative ideas and to support projects with high risk. Governments and nonprofits, for example, are beholden to voters or other stakeholders, whereas philanthropists are beholden only to the cause and to creating public good.

Support for traditional charities is important, but foundations should identify space within their portfolios across all program areas to support innovation and new ideas. Unless we support new concepts and approaches to effecting change, we are likely to continue with the same limited outcomes.

Haile Johnston, Co-founder, The Common Market

This sentiment also came through in our in-depth interviews. Said Haile Johnston, co-founder of The Common Market, a nonprofit that connects communities with sustainable family farms: “Support for traditional charities is important, but foundations should identify space within their portfolios across all program areas to support innovation and new ideas. Unless we support new concepts and approaches to effecting change, we are likely to continue with the same limited outcomes.”

Managing Risk Through Accountability

With big risks come big rewards, as well as greater responsibility for transparency and course correction. For many of those we interviewed, this sharpens the need for a more considered approach to measurement.

Maryana Iskander is CEO at Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, a nonprofit that helps place first-time work seekers with South African employers. She notes the importance of capturing the right data to drive smart decisions. “There is a difference between being data-driven and data-intelligent,” she noted. “The question is not: Do you have data? It is: How do you use your data? Are you learning the right things?”

And it’s not just what you measure, but when. In addition to touting the ability to capture more nuanced data, our interview subjects noted that program evaluation can now be done in real-time, allowing organizations to more quickly adjust course as they navigate new waters. Stephen Mahony finds real-time measurement invaluable in his mission at JumpStart: “Waiting six months down the line is too late — you can’t respond, you can’t revise.”

There is a difference between being data-driven and data-intelligent. The question is not: Do you have data? It is: How do you use your data? Are you learning the right things?

Maryana Iskander, CEO, Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator

Many interviewees indicated a shift in the way organizations are approaching data collection, fueled in part by technological innovations that make it possible to collect data in a more targeted way. In fact, 40 percent of our survey respondents pointed to improved measurement practices as the most significant positive change brought about by technology disruption in the social impact space.

From Coordination to Collaboration

Philanthropists are looking for new ways to collaborate with others to achieve results — across sectors, disciplines, and geographic boundaries.

Over 80 percent of our survey respondents said building partnerships with a common vision is critical for effective social impact work. And within those partnerships, impact practitioners increasingly recognize that a diversity of talent and perspectives is key to accelerating progress.

Breaking Down Traditional Boundaries

Based on our research, today’s impact professionals recognize the power of cross-disciplinary approaches in addressing tough social challenges. In fact, we’re seeing a renewed emphasis on collaboration between organizations with vastly different capabilities, approaches, and purviews.

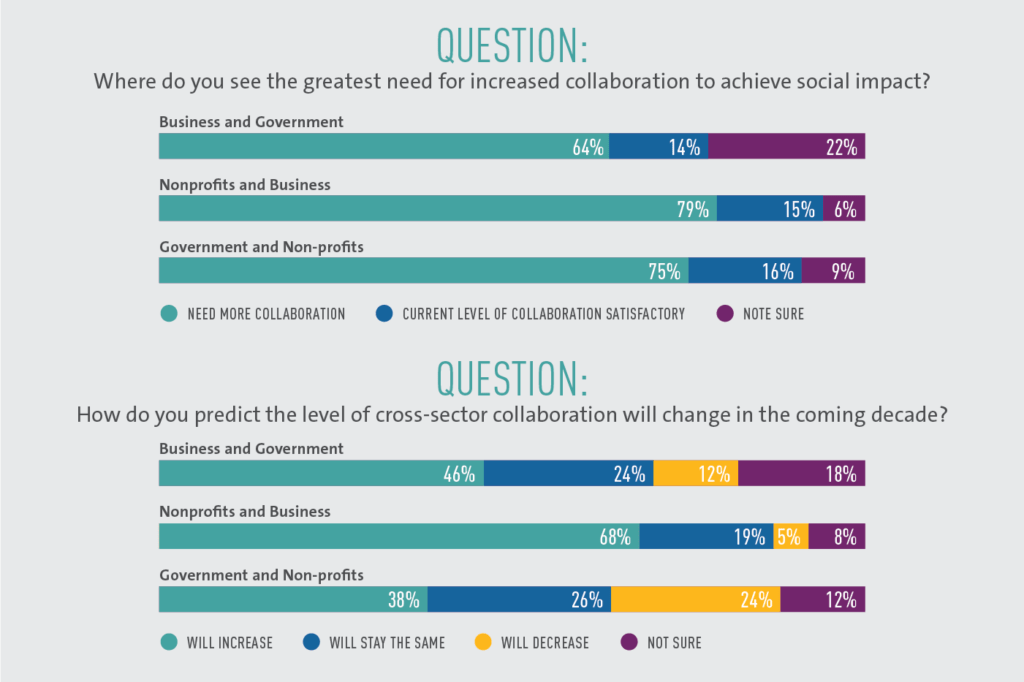

Among our survey respondents, 79 percent said they want to see more business-nonprofit collaboration, 75 percent want to see more government-nonprofit collaboration, and 64 percent want to see more business-government collaboration. Their outlook on whether those collaborations would actually happen, though, was more pessimistic: Less than half believe cooperation between governments and nonprofits will increase in the next decade. A quarter of respondents expect it to decrease.

Erin Mote of Brooklyn LAB and InnovateEDU notes that the keys to successful cross-sector partnerships are authenticity, transparency, and trust. “Every time I engage in a partnership, I ask: What are we not saying? What is the elephant in the room? What do we need to acknowledge?”

Mote added, “Often the most critical question we need to ask ourselves when we are making decisions is: Who is not at this table?” That’s the kind of question future philanthropists will ask to ensure that they’re actively pursuing diverse perspectives and experiences in their collaborations and partnerships.

Collaboration Through Sharing — Failures and All

In our survey, respondents noted the importance of several different modes of collaboration, from knowledge and information sharing to resource pooling and coordinating activities on the ground. Of these, knowledge and information sharing was the most cited, with 68 percent of respondents listing it as a requirement for effective partnerships in the future. Nearly one-third (31 percent) of respondents pointed specifically to information sharing as the most significant positive change that technological innovation has brought to the impact space.

This desire for sharing even carries over to missteps and failures. Our survey revealed a disconnect, however, between the ideal and the reality. Although 76 percent of respondents indicated it is most useful for organizations to share their failures and pitfalls in achieving impact, only 14 percent said their peer organizations consistently exercise that habit. Overall, we’re more tight-lipped about failure than we think we should be.

It’s understandable, given that no one wants to let down their beneficiaries or look like they’ve got nothing to show for all the resources they’ve spent. But now we know that three-fourths of our peers don’t actually consider “failure” a waste. They can learn something valuable from your story, even if it’s not the success you aimed for. “The more ideas we share, the quicker we advance as a collective,” said The Common Market’s Haile Johnston.

From Quick Fixes to Long Term-Ism

Philanthropists are increasingly called on to take a long view, building lasting relationships with their causes and partners, and focusing on leverage rather than quick solutions.

If we are to make progress against deeply entrenched societal issues, the long view is the only one we can afford to take. More than 50 percent of our survey respondents identified a long-term view as the single most important trait that will define effective philanthropists of the future.

Targeting Systemic Change

Why is a long-term perspective so important? According to 53 percent of our survey respondents, it’s because the only impact that counts is impact that lasts — and lasting impact is rarely achieved overnight.

Akshay Saxena takes the long view with Avanti Learning Centres, a social enterprise that runs India’s largest and most successful network of science and mathematics classrooms. “For us to dramatically transform science and math education, teachers must drive systemic reform within both the public and private school systems,” he notes. He knows that kind of reform takes time, but it is achievable — even within the next 10 years. “I would not do the work if I didn’t have that vision.”

A Call for “Stubborn Patience”

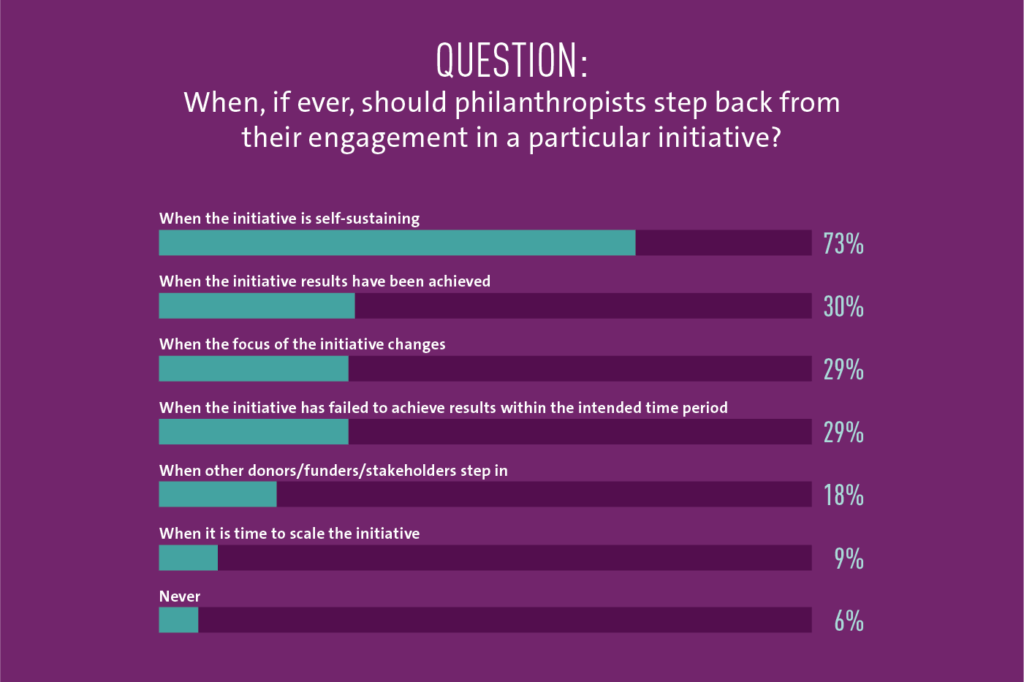

Big shifts require many small steps, and some stumbles. More than 70 percent of our survey respondents believe philanthropists should stick with the work even when initiatives fail to reach results within a given time, or when the focus of the project changes.

“I think we need more patient capital,” said Thato Kgatlhanye, founder of Repurpose Schoolbags in South Africa, which uses tech-infused school bags to help children study after dark. “We’re not just doing manufacturing, but also dealing with quite a lot of social and psychological factors. In this kind of work, you need patience.”

Hiccups and detours can be tempting reasons to call it quits, but respondents believe we have to adjust and keep trying. Nearly three-quarters of our respondents feel the work should only stop when the initiative is self-sustaining. Even more of them (85 percent) said that long-term results are the most important measure of the work. Were the project or aspects of the project successful? If they weren’t, why not? Were lives positively impacted? We can only answer those questions if we see it through in the long term.

The Dell Social Impact Principles

At the end of a readout or report like this, the natural question is, “So what do we do?” At the foundation, we’ve asked that of ourselves again and again over the past 18 years.

The findings in this report validate many of the views and commitments that have come out of our own experience and introspection. Therefore, we want to close by sharing eight principles that guide our work and hold us accountable to doing it effectively and honorably.

We hope the research in this report and these principles offer a window into how you might start or continue your journey toward lasting change in the world. Rather than a prescription, treat them as a starting point. For conversation, if nothing else. What works for us can work for anyone.